A CBC Casper Tutorial

2018 Dec 05

See all posts

A CBC Casper Tutorial

Special thanks to Vlad Zamfir, Aditya Asgaonkar, Ameen Soleimani and Jinglan Wang for review

In order to help more people understand "the other Casper" (Vlad Zamfir's CBC Casper), and specifically the instantiation that works best for blockchain protocols, I thought that I would write an explainer on it myself, from a less abstract and more "close to concrete usage" point of view. Vlad's descriptions of CBC Casper can be found here and here and here; you are welcome and encouraged to look through these materials as well.

CBC Casper is designed to be fundamentally very versatile and abstract, and come to consensus on pretty much any data structure; you can use CBC to decide whether to choose 0 or 1, you can make a simple block-by-block chain run on top of CBC, or a \(2^{92}\)-dimensional hypercube tangle DAG, and pretty much anything in between.

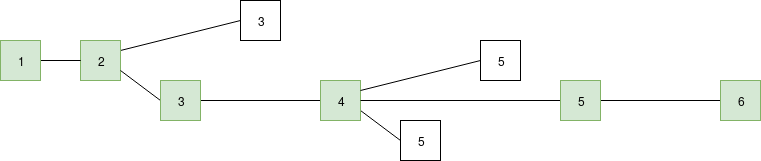

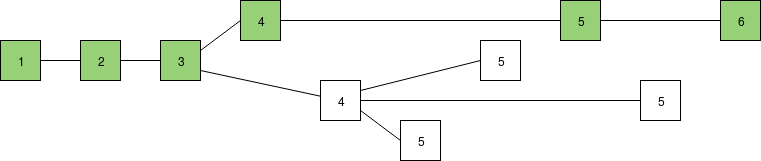

But for simplicity, we will first focus our attention on one concrete case: a simple chain-based structure. We will suppose that there is a fixed validator set consisting of \(N\) validators (a fancy word for "staking nodes"; we also assume that each node is staking the same amount of coins, cases where this is not true can be simulated by assigning some nodes multiple validator IDs), time is broken up into ten-second slots, and validator \(k\) can create a block in slot \(k\), \(N + k\), \(2N + k\), etc. Each block points to one specific parent block. Clearly, if we wanted to make something maximally simple, we could just take this structure, impose a longest chain rule on top of it, and call it a day.

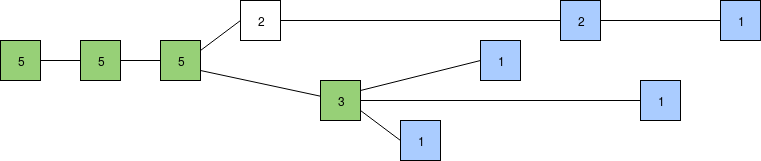

The green chain is the longest chain (length 6) so it is considered to be the "canonical chain".

However, what we care about here is adding some notion of "finality" - the idea that some block can be so firmly established in the chain that it cannot be overtaken by a competing block unless a very large portion (eg. \(\frac{1}{4}\)) of validators commit a uniquely attributable fault - act in some way which is clearly and cryptographically verifiably malicious. If a very large portion of validators do act maliciously to revert the block, proof of the misbehavior can be submitted to the chain to take away those validators' entire deposits, making the reversion of finality extremely expensive (think hundreds of millions of dollars).

LMD GHOST

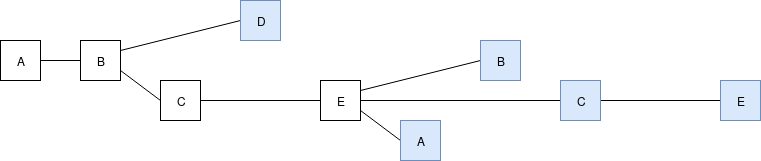

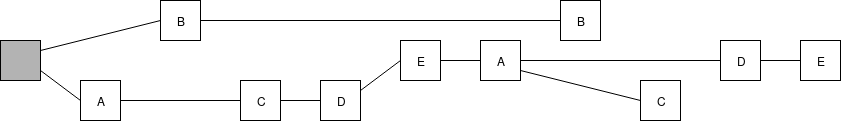

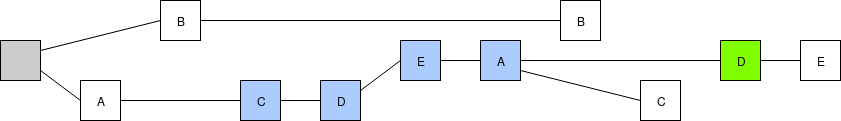

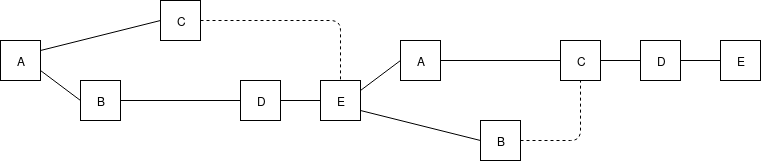

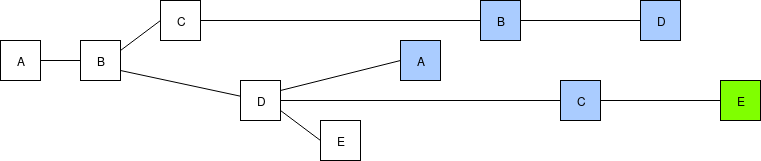

We will take this one step at a time. First, we replace the fork choice rule (the rule that chooses which chain among many possible choices is "the canonical chain", ie. the chain that users should care about), moving away from the simple longest-chain-rule and instead using "latest message driven GHOST". To show how LMD GHOST works, we will modify the above example. To make it more concrete, suppose the validator set has size 5, which we label \(A\), \(B\), \(C\), \(D\), \(E\), so validator \(A\) makes the blocks at slots 0 and 5, validator \(B\) at slots 1 and 6, etc. A client evaluating the LMD GHOST fork choice rule cares only about the most recent (ie. highest-slot) message (ie. block) signed by each validator:

Latest messages in blue, slots from left to right (eg. \(A\)'s block on the left is at slot 0, etc.)

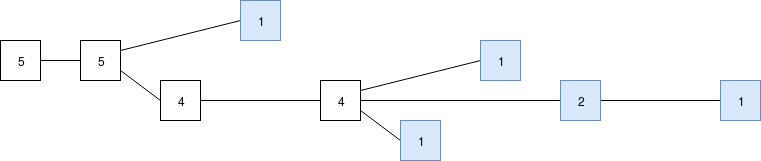

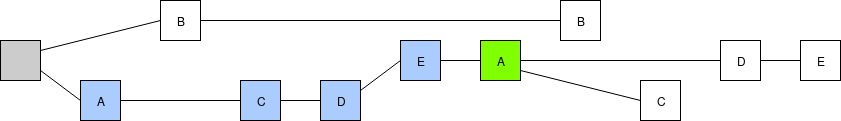

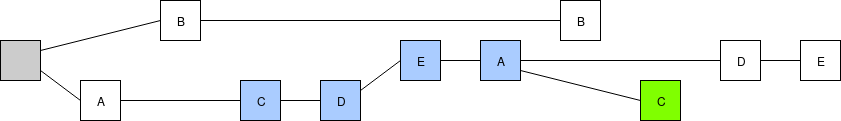

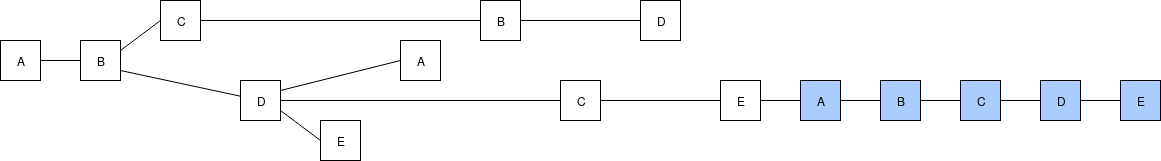

Now, we will use only these messages as source data for the "greedy heaviest observed subtree" (GHOST) fork choice rule: start at the genesis block, then each time there is a fork choose the side where more of the latest messages support that block's subtree (ie. more of the latest messages support either that block or one of its descendants), and keep doing this until you reach a block with no children. We can compute for each block the subset of latest messages that support either the block or one of its descendants:

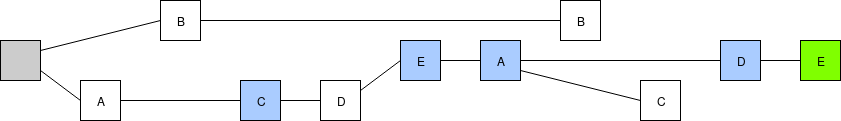

Now, to compute the head, we start at the beginning, and then at each fork pick the higher number: first, pick the bottom chain as it has 4 latest messages supporting it versus 1 for the single-block top chain, then at the next fork support the middle chain. The result is the same longest chain as before. Indeed, in a well-running network (ie. the orphan rate is low), almost all of the time LMD GHOST and the longest chain rule will give the exact same answer. But in more extreme circumstances, this is not always true. For example, consider the following chain, with a more substantial three-block fork:

Scoring blocks by chain length. If we follow the longest chain rule, the top chain is longer, so the top chain wins.

Scoring blocks by number of supporting latest messages and using the GHOST rule (latest message from each validator shown in blue). The bottom chain has more recent support, so if we follow the LMD GHOST rule the bottom chain wins, though it's not yet clear which of the three blocks takes precedence.

The LMD GHOST approach is advantageous in part because it is better at extracting information in conditions of high latency. If two validators create two blocks with the same parent, they should really be both counted as cooperating votes for the parent block, even though they are at the same time competing votes for themselves. The longest chain rule fails to capture this nuance; GHOST-based rules do.

Detecting finality

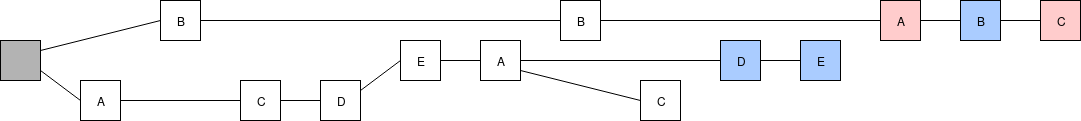

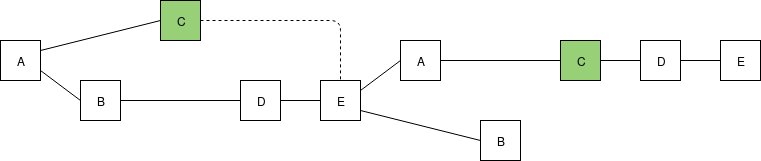

But the LMD GHOST approach has another nice property: it's sticky. For example, suppose that for two rounds, \(\frac{4}{5}\) of validators voted for the same chain (we'll assume that the one of the five validators that did not, \(B\), is attacking):

What would need to actually happen for the chain on top to become the canonical chain? Four of five validators built on top of \(E\)'s first block, and all four recognized that \(E\) had a high score in the LMD fork choice. Just by looking at the structure of the chain, we can know for a fact at least some of the messages that the validators must have seen at different times. Here is what we know about the four validators' views:

A's view

|

C's view

|

D's view

|

E's view

|

Blocks produced by each validator in green, the latest messages we know that they saw from each of the other validators in blue.

Note that all four of the validators could have seen one or both of \(B\)'s blocks, and \(D\) and \(E\) could have seen \(C\)'s second block, making that the latest message in their views instead of \(C\)'s first block; however, the structure of the chain itself gives us no evidence that they actually did. Fortunately, as we will see below, this ambiguity does not matter for us.

\(A\)'s view contains four latest-messages supporting the bottom chain, and none supporting \(B\)'s block. Hence, in (our simulation of) \(A\)'s eyes the score in favor of the bottom chain is at least 4-1. The views of \(C\), \(D\) and \(E\) paint a similar picture, with four latest-messages supporting the bottom chain. Hence, all four of the validators are in a position where they cannot change their minds unless two other validators change their minds first to bring the score to 2-3 in favor of \(B\)'s block.

Note that our simulation of the validators' views is "out of date" in that, for example, it does not capture that \(D\) and \(E\) could have seen the more recent block by \(C\). However, this does not alter the calculation for the top vs bottom chain, because we can very generally say that any validator's new message will have the same opinion as their previous messages, unless two other validators have already switched sides first.

A minimal viable attack. \(A\) and \(C\) illegally switch over to support \(B\)'s block (and can get penalized for this), giving it a 3-2 advantage, and at this point it becomes legal for \(D\) and \(E\) to also switch over.

Since fork choice rules such as LMD GHOST are sticky in this way, and clients can detect when the fork choice rule is "stuck on" a particular block, we can use this as a way of achieving asynchronously safe consensus.

Safety Oracles

Actually detecting all possible situations where the chain becomes stuck on some block (in CBC lingo, the block is "decided" or "safe") is very difficult, but we can come up with a set of heuristics ("safety oracles") which will help us detect some of the cases where this happens. The simplest of these is the clique oracle. If there exists some subset \(V\) of the validators making up portion \(p\) of the total validator set (with \(p > \frac{1}{2}\)) that all make blocks supporting some block \(B\) and then make another round of blocks still supporting \(B\) that references their first round of blocks, then we can reason as follows:

Because of the two rounds of messaging, we know that this subset \(V\) all (i) support \(B\) (ii) know that \(B\) is well-supported, and so none of them can legally switch over unless enough others switch over first. For some competing \(B'\) to beat out \(B\), the support such a \(B'\) can legally have is initially at most \(1-p\) (everyone not part of the clique), and to win the LMD GHOST fork choice its support needs to get to \(\frac{1}{2}\), so at least \(\frac{1}{2} - (1-p) = p - \frac{1}{2}\) need to illegally switch over to get it to the point where the LMD GHOST rule supports \(B'\).

As a specific case, note that the \(p=\frac{3}{4}\) clique oracle offers a \(\frac{1}{4}\) level of safety, and a set of blocks satisfying the clique can (and in normal operation, will) be generated as long as \(\frac{3}{4}\) of nodes are online. Hence, in a BFT sense, the level of fault tolerance that can be reached using two-round clique oracles is \(\frac{1}{3}\), in terms of both liveness and safety.

This approach to consensus has many nice benefits. First of all, the short-term chain selection algorithm, and the "finality algorithm", are not two awkwardly glued together distinct components, as they admittedly are in Casper FFG; rather, they are both part of the same coherent whole. Second, because safety detection is client-side, there is no need to choose any thresholds in-protocol; clients can decide for themselves what level of safety is sufficient to consider a block as finalized.

Going Further

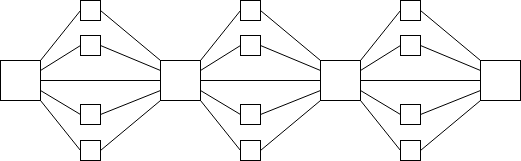

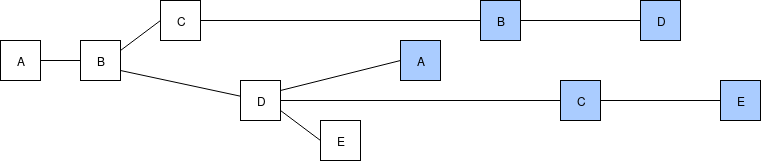

CBC can be extended further in many ways. First, one can come up with other safety oracles; higher-round clique oracles can reach \(\frac{1}{3}\) fault tolerance. Second, we can add validator rotation mechanisms. The simplest is to allow the validator set to change by a small percentage every time the \(q=\frac{3}{4}\) clique oracle is satisfied, but there are other things that we can do as well. Third, we can go beyond chain-like structures, and instead look at structures that increase the density of messages per unit time, like the Serenity beacon chain's attestation structure:

In this case, it becomes worthwhile to separate attestations from blocks; a block is an object that actually grows the underlying DAG, whereas an attestation contributes to the fork choice rule. In the Serenity beacon chain spec, each block may have hundreds of attestations corresponding to it. However, regardless of which way you do it, the core logic of CBC Casper remains the same.

To make CBC Casper's safety "cryptoeconomically enforceable", we need to add validity and slashing conditions. First, we'll start with the validity rule. A block contains both a parent block and a set of attestations that it knows about that are not yet part of the chain (similar to "uncles" in the current Ethereum PoW chain). For the block to be valid, the block's parent must be the result of executing the LMD GHOST fork choice rule given the information included in the chain including in the block itself.

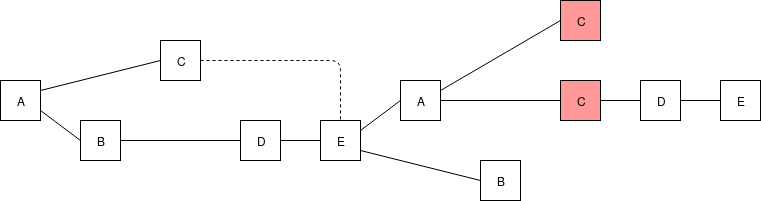

Dotted lines are uncle links, eg. when E creates a block, E notices that C is not yet part of the chain, and so includes a reference to C.

We now can make CBC Casper safe with only one slashing condition: you cannot make two attestations \(M_1\) and \(M_2\), unless either \(M_1\) is in the chain that \(M_2\) is attesting to or \(M_2\) is in the chain that \(M_2\) is attesting to.

OK

|

Not OK

|

The validity and slashing conditions are relatively easy to describe, though actually implementing them requires checking hash chains and executing fork choice rules in-consensus, so it is not nearly as simple as taking two messages and checking a couple of inequalities between the numbers that these messages commit to, as you can do in Casper FFG for the NO_SURROUND and NO_DBL_VOTE slashing conditions.

Liveness in CBC Casper piggybacks off of the liveness of whatever the underlying chain algorithm is (eg. if it's one-block-per-slot, then it depends on a synchrony assumption that all nodes will see everything produced in slot \(N\) before the start of slot \(N+1\)). It's not possible to get "stuck" in such a way that one cannot make progress; it's possible to get to the point of finalizing new blocks from any situation, even one where there are attackers and/or network latency is higher than that required by the underlying chain algorithm.

Suppose that at some time \(T\), the network "calms down" and synchrony assumptions are once again satisfied. Then, everyone will converge on the same view of the chain, with the same head \(H\). From there, validators will begin to sign messages supporting \(H\) or descendants of \(H\). From there, the chain can proceed smoothly, and will eventually satisfy a clique oracle, at which point \(H\) becomes finalized.

Chaotic network due to high latency.

Network latency subsides, a majority of validators see all of the same blocks or at least enough of them to get to the same head when executing the fork choice, and start building on the head, further reinforcing its advantage in the fork choice rule.

Chain proceeds "peacefully" at low latency. Soon, a clique oracle will be satisfied.

That's all there is to it! Implementation-wise, CBC may arguably be considerably more complex than FFG, but in terms of ability to reason about the protocol, and the properties that it provides, it's surprisingly simple.

A CBC Casper Tutorial

2018 Dec 05 See all postsSpecial thanks to Vlad Zamfir, Aditya Asgaonkar, Ameen Soleimani and Jinglan Wang for review

In order to help more people understand "the other Casper" (Vlad Zamfir's CBC Casper), and specifically the instantiation that works best for blockchain protocols, I thought that I would write an explainer on it myself, from a less abstract and more "close to concrete usage" point of view. Vlad's descriptions of CBC Casper can be found here and here and here; you are welcome and encouraged to look through these materials as well.

CBC Casper is designed to be fundamentally very versatile and abstract, and come to consensus on pretty much any data structure; you can use CBC to decide whether to choose 0 or 1, you can make a simple block-by-block chain run on top of CBC, or a \(2^{92}\)-dimensional hypercube tangle DAG, and pretty much anything in between.

But for simplicity, we will first focus our attention on one concrete case: a simple chain-based structure. We will suppose that there is a fixed validator set consisting of \(N\) validators (a fancy word for "staking nodes"; we also assume that each node is staking the same amount of coins, cases where this is not true can be simulated by assigning some nodes multiple validator IDs), time is broken up into ten-second slots, and validator \(k\) can create a block in slot \(k\), \(N + k\), \(2N + k\), etc. Each block points to one specific parent block. Clearly, if we wanted to make something maximally simple, we could just take this structure, impose a longest chain rule on top of it, and call it a day.

The green chain is the longest chain (length 6) so it is considered to be the "canonical chain".

However, what we care about here is adding some notion of "finality" - the idea that some block can be so firmly established in the chain that it cannot be overtaken by a competing block unless a very large portion (eg. \(\frac{1}{4}\)) of validators commit a uniquely attributable fault - act in some way which is clearly and cryptographically verifiably malicious. If a very large portion of validators do act maliciously to revert the block, proof of the misbehavior can be submitted to the chain to take away those validators' entire deposits, making the reversion of finality extremely expensive (think hundreds of millions of dollars).

LMD GHOST

We will take this one step at a time. First, we replace the fork choice rule (the rule that chooses which chain among many possible choices is "the canonical chain", ie. the chain that users should care about), moving away from the simple longest-chain-rule and instead using "latest message driven GHOST". To show how LMD GHOST works, we will modify the above example. To make it more concrete, suppose the validator set has size 5, which we label \(A\), \(B\), \(C\), \(D\), \(E\), so validator \(A\) makes the blocks at slots 0 and 5, validator \(B\) at slots 1 and 6, etc. A client evaluating the LMD GHOST fork choice rule cares only about the most recent (ie. highest-slot) message (ie. block) signed by each validator:

Latest messages in blue, slots from left to right (eg. \(A\)'s block on the left is at slot 0, etc.)

Now, we will use only these messages as source data for the "greedy heaviest observed subtree" (GHOST) fork choice rule: start at the genesis block, then each time there is a fork choose the side where more of the latest messages support that block's subtree (ie. more of the latest messages support either that block or one of its descendants), and keep doing this until you reach a block with no children. We can compute for each block the subset of latest messages that support either the block or one of its descendants:

Now, to compute the head, we start at the beginning, and then at each fork pick the higher number: first, pick the bottom chain as it has 4 latest messages supporting it versus 1 for the single-block top chain, then at the next fork support the middle chain. The result is the same longest chain as before. Indeed, in a well-running network (ie. the orphan rate is low), almost all of the time LMD GHOST and the longest chain rule will give the exact same answer. But in more extreme circumstances, this is not always true. For example, consider the following chain, with a more substantial three-block fork:

Scoring blocks by chain length. If we follow the longest chain rule, the top chain is longer, so the top chain wins.

Scoring blocks by number of supporting latest messages and using the GHOST rule (latest message from each validator shown in blue). The bottom chain has more recent support, so if we follow the LMD GHOST rule the bottom chain wins, though it's not yet clear which of the three blocks takes precedence.

The LMD GHOST approach is advantageous in part because it is better at extracting information in conditions of high latency. If two validators create two blocks with the same parent, they should really be both counted as cooperating votes for the parent block, even though they are at the same time competing votes for themselves. The longest chain rule fails to capture this nuance; GHOST-based rules do.

Detecting finality

But the LMD GHOST approach has another nice property: it's sticky. For example, suppose that for two rounds, \(\frac{4}{5}\) of validators voted for the same chain (we'll assume that the one of the five validators that did not, \(B\), is attacking):

What would need to actually happen for the chain on top to become the canonical chain? Four of five validators built on top of \(E\)'s first block, and all four recognized that \(E\) had a high score in the LMD fork choice. Just by looking at the structure of the chain, we can know for a fact at least some of the messages that the validators must have seen at different times. Here is what we know about the four validators' views:

A's view

C's view

D's view

E's view

Note that all four of the validators could have seen one or both of \(B\)'s blocks, and \(D\) and \(E\) could have seen \(C\)'s second block, making that the latest message in their views instead of \(C\)'s first block; however, the structure of the chain itself gives us no evidence that they actually did. Fortunately, as we will see below, this ambiguity does not matter for us.

\(A\)'s view contains four latest-messages supporting the bottom chain, and none supporting \(B\)'s block. Hence, in (our simulation of) \(A\)'s eyes the score in favor of the bottom chain is at least 4-1. The views of \(C\), \(D\) and \(E\) paint a similar picture, with four latest-messages supporting the bottom chain. Hence, all four of the validators are in a position where they cannot change their minds unless two other validators change their minds first to bring the score to 2-3 in favor of \(B\)'s block.

Note that our simulation of the validators' views is "out of date" in that, for example, it does not capture that \(D\) and \(E\) could have seen the more recent block by \(C\). However, this does not alter the calculation for the top vs bottom chain, because we can very generally say that any validator's new message will have the same opinion as their previous messages, unless two other validators have already switched sides first.

A minimal viable attack. \(A\) and \(C\) illegally switch over to support \(B\)'s block (and can get penalized for this), giving it a 3-2 advantage, and at this point it becomes legal for \(D\) and \(E\) to also switch over.

Since fork choice rules such as LMD GHOST are sticky in this way, and clients can detect when the fork choice rule is "stuck on" a particular block, we can use this as a way of achieving asynchronously safe consensus.

Safety Oracles

Actually detecting all possible situations where the chain becomes stuck on some block (in CBC lingo, the block is "decided" or "safe") is very difficult, but we can come up with a set of heuristics ("safety oracles") which will help us detect some of the cases where this happens. The simplest of these is the clique oracle. If there exists some subset \(V\) of the validators making up portion \(p\) of the total validator set (with \(p > \frac{1}{2}\)) that all make blocks supporting some block \(B\) and then make another round of blocks still supporting \(B\) that references their first round of blocks, then we can reason as follows:

Because of the two rounds of messaging, we know that this subset \(V\) all (i) support \(B\) (ii) know that \(B\) is well-supported, and so none of them can legally switch over unless enough others switch over first. For some competing \(B'\) to beat out \(B\), the support such a \(B'\) can legally have is initially at most \(1-p\) (everyone not part of the clique), and to win the LMD GHOST fork choice its support needs to get to \(\frac{1}{2}\), so at least \(\frac{1}{2} - (1-p) = p - \frac{1}{2}\) need to illegally switch over to get it to the point where the LMD GHOST rule supports \(B'\).

As a specific case, note that the \(p=\frac{3}{4}\) clique oracle offers a \(\frac{1}{4}\) level of safety, and a set of blocks satisfying the clique can (and in normal operation, will) be generated as long as \(\frac{3}{4}\) of nodes are online. Hence, in a BFT sense, the level of fault tolerance that can be reached using two-round clique oracles is \(\frac{1}{3}\), in terms of both liveness and safety.

This approach to consensus has many nice benefits. First of all, the short-term chain selection algorithm, and the "finality algorithm", are not two awkwardly glued together distinct components, as they admittedly are in Casper FFG; rather, they are both part of the same coherent whole. Second, because safety detection is client-side, there is no need to choose any thresholds in-protocol; clients can decide for themselves what level of safety is sufficient to consider a block as finalized.

Going Further

CBC can be extended further in many ways. First, one can come up with other safety oracles; higher-round clique oracles can reach \(\frac{1}{3}\) fault tolerance. Second, we can add validator rotation mechanisms. The simplest is to allow the validator set to change by a small percentage every time the \(q=\frac{3}{4}\) clique oracle is satisfied, but there are other things that we can do as well. Third, we can go beyond chain-like structures, and instead look at structures that increase the density of messages per unit time, like the Serenity beacon chain's attestation structure:

In this case, it becomes worthwhile to separate attestations from blocks; a block is an object that actually grows the underlying DAG, whereas an attestation contributes to the fork choice rule. In the Serenity beacon chain spec, each block may have hundreds of attestations corresponding to it. However, regardless of which way you do it, the core logic of CBC Casper remains the same.

To make CBC Casper's safety "cryptoeconomically enforceable", we need to add validity and slashing conditions. First, we'll start with the validity rule. A block contains both a parent block and a set of attestations that it knows about that are not yet part of the chain (similar to "uncles" in the current Ethereum PoW chain). For the block to be valid, the block's parent must be the result of executing the LMD GHOST fork choice rule given the information included in the chain including in the block itself.

Dotted lines are uncle links, eg. when E creates a block, E notices that C is not yet part of the chain, and so includes a reference to C.

We now can make CBC Casper safe with only one slashing condition: you cannot make two attestations \(M_1\) and \(M_2\), unless either \(M_1\) is in the chain that \(M_2\) is attesting to or \(M_2\) is in the chain that \(M_2\) is attesting to.

OK

Not OK

The validity and slashing conditions are relatively easy to describe, though actually implementing them requires checking hash chains and executing fork choice rules in-consensus, so it is not nearly as simple as taking two messages and checking a couple of inequalities between the numbers that these messages commit to, as you can do in Casper FFG for the

NO_SURROUNDandNO_DBL_VOTEslashing conditions.Liveness in CBC Casper piggybacks off of the liveness of whatever the underlying chain algorithm is (eg. if it's one-block-per-slot, then it depends on a synchrony assumption that all nodes will see everything produced in slot \(N\) before the start of slot \(N+1\)). It's not possible to get "stuck" in such a way that one cannot make progress; it's possible to get to the point of finalizing new blocks from any situation, even one where there are attackers and/or network latency is higher than that required by the underlying chain algorithm.

Suppose that at some time \(T\), the network "calms down" and synchrony assumptions are once again satisfied. Then, everyone will converge on the same view of the chain, with the same head \(H\). From there, validators will begin to sign messages supporting \(H\) or descendants of \(H\). From there, the chain can proceed smoothly, and will eventually satisfy a clique oracle, at which point \(H\) becomes finalized.

Chaotic network due to high latency.

Network latency subsides, a majority of validators see all of the same blocks or at least enough of them to get to the same head when executing the fork choice, and start building on the head, further reinforcing its advantage in the fork choice rule.

Chain proceeds "peacefully" at low latency. Soon, a clique oracle will be satisfied.

That's all there is to it! Implementation-wise, CBC may arguably be considerably more complex than FFG, but in terms of ability to reason about the protocol, and the properties that it provides, it's surprisingly simple.