On Nathan Schneider on the limits of cryptoeconomics

2021 Sep 26

See all posts

On Nathan Schneider on the limits of cryptoeconomics

Nathan Schneider has recently released an article describing his perspectives on cryptoeconomics, and particularly on the limits of cryptoeconomic approaches to governance and what cryptoeconomics could be augmented with to improve its usefulness. This is, of course, a topic that is dear to me ([1] [2] [3] [4] [5]), so it is heartening to see someone else take the blockchain space seriously as an intellectual tradition and engage with the issues from a different and unique perspective.

The main question that Nathan's piece is trying to explore is simple. There is a large body of intellectual work that criticizes a bubble of concepts that they refer to as "economization", "neoliberalism" and similar terms, arguing that they corrode democratic political values and leave many people's needs unmet as a result. The world of cryptocurrency is very economic (lots of tokens flying around everywhere, with lots of functions being assigned to those tokens), very neo (the space is 12 years old!) and very liberal (freedom and voluntary participation are core to the whole thing). Do these critiques also apply to blockchain systems? If so, what conclusions should we draw, and how could blockchain systems be designed to account for these critiques? Nathan's answer: more hybrid approaches combining ideas from both economics and politics. But what will it actually take to achieve that, and will it give the results that we want? My answer: yes, but there's a lot of subtleties involved.

What are the critiques of neoliberalism and economic logic?

Near the beginning of Nathan's piece, he describes the critiques of overuse of economic logic briefly. That said, he does not go much further into the underlying critiques himself, preferring to point to other sources that have already covered the issue in depth:

The economics in cryptoeconomics raises a particular set of anxieties. Critics have long warned against the expansion of economic logics, crowding out space for vigorous politics in public life. From the Zapatista insurgents of southern Mexico (Hayden, 2002) to political theorists like William Davies (2014) and Wendy Brown (2015), the "neoliberal" aspiration for economics to guide all aspects of society represents a threat to democratic governance and human personhood itself. Here is Brown:

Neoliberalism transmogrifies every human domain and endeavor, along with humans themselves, according to a specific image of the economic. All conduct is economic conduct; all spheres of existence are framed and measured by economic terms and metrics, even when those spheres are not directly monetized. In neoliberal reason and in domains governed by it, we are only and everywhere homo oeconomicus (p. 10)

For Brown and other critics of neoliberalism, the ascent of the economic means the decline of the political—the space for collective determinations of the common good and the means of getting there.

At this point, it's worth pointing out that the "neoliberalism" being criticized here is not the same as the "neoliberalism" that is cheerfully promoted by the lovely folks at The Neoliberal Project; the thing being critiqued here is a kind of "enough two-party trade can solve everything" mentality, whereas The Neoliberal Project favors a mix of markets and democracy. But what is the thrust of the critique that Nathan is pointing to? What's the problem with everyone acting much more like homo oeconomicus? For this, we can take a detour and peek into the source, Wendy Brown's Undoing the Demos, itself. The book helpfully provides a list of the top "four deleterious effects" (the below are reformatted and abridged but direct quotes):

- Intensified inequality, in which the very top strata acquires and retains ever more wealth, the very bottom is literally turned out on the streets or into the growing urban and sub-urban slums of the world, while the middle strata works more hours for less pay, fewer benefits, less security...

- Crass or unethical commercialization of things and activities considered inappropriate for marketization. The claim is that marketization contributes to human exploitation or degradation, [...] limits or stratifies access to what ought to be broadly accessible and shared, [...] or because it enables something intrinsically horrific or severely denigrating to the planet.

- Ever-growing intimacy of corporate and finance capital with the state, and corporate domination of political decisions and economic policy

- Economic havoc wreaked on the economy by the ascendance and liberty of finance capital, especially the destabilizing effects of the inherent bubbles and other dramatic fluctuations of financial markets.

The bulk of Nathan's article follows along with analyses of how these issues affect DAOs and governance mechanisms within the crypto space specifically. Nathan focuses on three key problems:

- Plutocracy: "Those with more tokens than others hold more [I would add, disproportionately more] decision-making power than others..."

- Limited exposure to diverse motivations: "Cryptoeconomics sees only a certain slice of the people involved. Concepts such as self- sacrifice, duty, and honor are bedrock features of most political and business organizations, but difficult to simulate or approximate with cryptoeconomic incentive design"

- Positive and negative externalities: "Environmental costs are classic externalities—invisible to the feedback loops that the system understands and that communicate to its users as incentives ... the challenge of funding"public goods" is another example of an externality - and one that threatens the sustainability of crypteconomic systems"

The natural questions that arise for me are (i) to what extent do I agree with this critique at all and how it fits in with my own thinking, and (ii) how does this affect blockchains, and what do blockchain protocols need to actually do to avoid these traps?

What do I think of the critiques of neoliberalism generally?

I disagree with some, agree with others. I have always been suspicious of criticism of "crass and unethical commercialization", because it frequently feels like the author is attempting to launder their own feelings of disgust and aesthetic preferences into grand ethical and political ideologies - a sin common among all such ideologies, often the right (random example here) even more than the left. Back in the days when I had much less money and would sometimes walk a full hour to the airport to avoid a taxi fare, I remember thinking that I would love to get compensated for donating blood or using my body for clinical trials. And so to me, the idea that such transactions are inhuman exploitation has never been appealing.

But at the same time, I am far from a Walter Block-style defender of all locally-voluntary two-party commerce. I've written up my own viewpoints expressing similar concerns to parts of Wendy Brown's list in various articles:

So where does my own opposition to mixing finance and governance come from? This is a complicated topic, and my conclusions are in large part a result of my own failure after years of attempts to find a financialized governance mechanism that is economically stable. So here goes...

Finance is the absence of collusion prevention

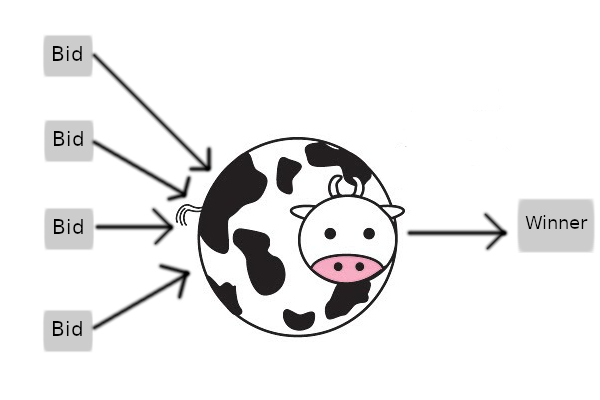

Out of the standard assumptions in what gets pejoratively called "spherical cow economics", people normally tend to focus on the unrealistic nature of perfect information and perfect rationality. But the unrealistic assumption that is hidden in the list that strikes me as even more misleading is individual choice: the idea that each agent is separately making their own decisions, no agent has a positive or negative stake in another agent's outcomes, and there are no "side games"; the only thing that sees each agent's decisions is the black box that we call "the mechanism".

This assumption is often used to bootstrap complex contraptions such as the VCG mechanism, whose theoretical optimality is based on beautiful arguments that because the price each player pays only depends on other players' bids, each player has no incentive to make a bid that does not reflect their true value in order to manipulate the price. A beautiful argument in theory, but it breaks down completely once you introduce the possibility that even two of the players are either allies or adversaries outside the mechanism.

Economics, and economics-inspired philosophy, is great at describing the complexities that arise when the number of players "playing the game" increases from one to two (see the tale of Crusoe and Friday in Murray Rothbard's The Ethics of Liberty for one example). But what this philosophical tradition completely misses is that going up to three players adds an even further layer of complexity. In an interaction between two people, the two can ignore each other, fight or trade. In an interaction between three people, there exists a new strategy: any two of the three can communicate and band together to gang up on the third. Three is the smallest denominator where it's possible to talk about a 51%+ attack that has someone outside the clique to be a victim.

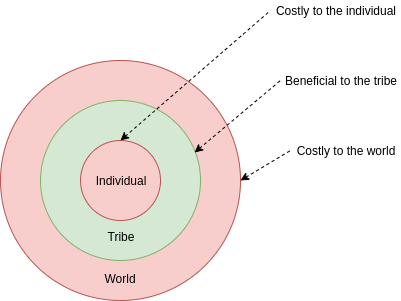

When there's only two people, more coordination can only be good. But once there's three people, the wrong kind of coordination can be harmful, and techniques to prevent harmful coordination (including decentralization itself) can become very valuable. And it's this management of coordination that is the essence of "politics".

Going from two people to three introduces the possibility of harms from unbalanced coordination: it's not just "the individual versus the group", it's "the individual versus the group versus the world".

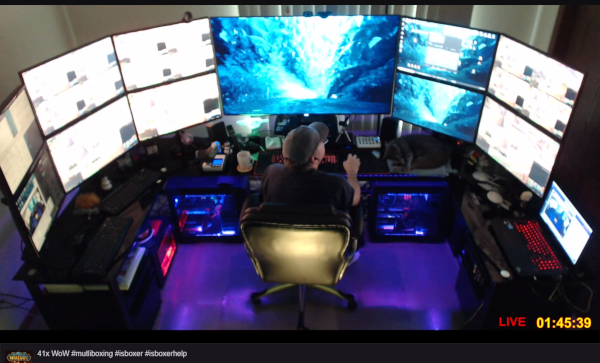

Now, we can understand try to use this framework to understand the pitfalls of "finance". Finance can be viewed as a set of patterns that naturally emerge in many kinds of systems that do not attempt to prevent collusion. Any system which claims to be non-finance, but does not actually make an effort to prevent collusion, will eventually acquire the characteristics of finance, if not something worse. To see why this is the case, compare two point systems we are all familiar with: money, and Twitter likes. Both kinds of points are valuable for extrinsic reasons, both have inevitably become status symbols, and both are number games where people spend a lot of time optimizing to try to get a higher score. And yet, they behave very differently. So what's the fundamental difference between the two?

The answer is simple: it's the lack of an efficient market to enable agreements like "I like your tweet if you like mine", or "I like your tweet if you pay me in some other currency". If such a market existed and was easy to use, Twitter would collapse completely (something like hyperinflation would happen, with the likely outcome that everyone would run automated bots that like every tweet to claim rewards), and even the likes-for-money markets that exist illicitly today are a big problem for Twitter. With money, however, "I send X to you if you send Y to me" is not an attack vector, it's just a boring old currency exchange transaction. A Twitter clone that does not prevent like-for-like markets would "hyperinflate" into everyone liking everything, and if that Twitter clone tried to stop the hyperinflation by limiting the number of likes each user can make, the likes would behave like a currency, and the end result would behave the same as if Twitter just added a tipping feature.

So what's the problem with finance? Well, if finance is optimized and structured collusion, then we can look for places where finance causes problems by using our existing economic tools to understand which mechanisms break if you introduce collusion! Unfortunately, governance by voting is a central example of this category; I've covered why in the "moving beyond coin voting governance" post and many other occasions. Even worse, cooperative game theory suggests that there might be no possible way to make a fully collusion-resistant governance mechanism.

And so we get the fundamental conundrum: the cypherpunk spirit is fundamentally about making maximally immutable systems that work with as little information as possible about who is participating ("on the internet, nobody knows you're a dog"), but making new forms of governance requires the system to have richer information about its participants and ability to dynamically respond to attacks in order to remain stable in the face of actors with unforeseen incentives. Failure to do this means that everything looks like finance, which means, well.... perennial over-representation of concentrated interests, and all the problems that come as a result.

On the internet, nobody knows if you're 0.0244 of a dog (image source). But what does this mean for governance?

The central role of collusion in understanding the difference between Kleros and regular courts

Now, let us get back to Nathan's article. The distinction between financial and non-financial mechanisms is key in the article. Let us start off with a description of the Kleros court:

The jurors stood to earn rewards by correctly choosing the answer that they expected other jurors to independently select. This process implements the "Schelling point" concept in game theory (Aouidef et al., 2021; Dylag & Smith, 2021). Such a jury does not deliberate, does not seek a common good together; its members unite through self-interest. Before coming to the jury, the factual basis of the case was supposed to come not from official organs or respected news organizations but from anonymous users similarly disciplined by reward-seeking. The prediction market itself was premised on the supposition that people make better forecasts when they stand to gain or lose the equivalent of money in the process. The politics of the presidential election in question, here, had been thoroughly transmuted into a cluster of economies.

The implicit critique is clear: the Kleros court is ultimately motivated to make decisions not on the basis of their "true" correctness or incorrectness, but rather on the basis of their financial interests. If Kleros is deciding whether Biden or Trump won the 2020 election, and one Kleros juror really likes Trump, precommits to voting in his favor, and bribes other jurors to vote the same way, other jurors are likely to fall in line because of Kleros's conformity incentives: jurors are rewarded if their vote agrees with the majority vote, and penalized otherwise. The theoretical answer to this is the right to exit: if the majority of Kleros jurors vote to proclaim that Trump won the election, a minority can spin off a fork of Kleros where Biden is considered to have won, and their fork may well get a higher market price than the original. Sometimes, this actually works! But, as Nathan points out, it is not always so simple:

But exit may not be as easy as it appears, whether it be from a social-media network or a protocol. The persistent dominance of early-to-market blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum suggests that cryptoeconomics similarly favors incumbency.

But alongside the implicit critique is an implicit promise: that regular courts are somehow able to rise above self-interest and "seek a common good together" and thereby avoid some of these failure modes. What is it that financialized Kleros courts lack, but non-financialized regular courts retain, that makes them more robust? One possible answer is that courts lack Kleros's explicit conformity incentive. But if you just take Kleros as-is, remove the conformity incentive (say, there's a reward for voting that does not depend on how you vote), and do nothing else, you risk creating even more problems. Kleros judges could get lazy, but more importantly if there's no incentive at all to choose how you vote, even the tiniest bribe could affect a judge's decision.

So now we get to the real answer: the key difference between financialized Kleros courts and non-financialized regular courts is that financialized Kleros courts are, well... financialized. They make no effort to explicitly prevent collusion. Non-financialized courts, on the other hand, do prevent collusion in two key ways:

- Bribing a judge to vote in a particular way is explicitly illegal

- The judge position itself is non-fungible. It gets awarded to specific carefully-selected individuals, and they cannot simply go and sell or reallocate their entire judging rights and salary to someone else.

The only reason why political and legal systems work is that a lot of hard thinking and work has gone on behind the scenes to insulate the decision-makers from extrinsic incentives, and punish them explicitly if they are discovered to be accepting incentives from the outside. The lack of extrinsic motivation allows the intrinsic motivation to shine through. Furthermore, the lack of transferability allows governance power to be given to specific actors whose intrinsic motivations we trust, avoiding governance power always flowing to "the highest bidder". But in the case of Kleros, the lack of hostile extrinsic motivation cannot be guaranteed, and transferability is unavoidable, and so overpoweringly strong in-mechanism extrinsic motivation (the conformity incentive) was the best solution they could find to deal with the problem.

And of course, the "final backstop" that Kleros relies on, the right of users to fork away, itself depends on social coordination to take place - a messy and difficult institution, often derided by cryptoeconomic purists as "proof of social media", that works precisely because public discussion has lots of informal collusion detection and prevention all over the place.

Collusion in understanding DAO governance issues

But what happens when there is no single right answer that they can expect voters to converge on? This is where we move away from adjudication and toward governance (yes, I know that adjudication has unavoidably grey edge cases too. Governance just has them much more often). Nathan writes:

Governance by economics is nothing new. Joint-stock companies conventionally operate on plutocratic governance—more shares equals more votes. This arrangement is economically efficient for aligning shareholder interests (Davidson and Potts, this issue), even while it may sideline such externalities as fair wages and environmental impacts...

In my opinion, this actually concedes too much! Governance by economics is not "efficient" once you drop the spherical-cow assumption of no collusion, because it is inherently vulnerable to 51% of the stakeholders colluding to liquidate the company and split its resources among themselves. The only reason why this does not happen much more often "in real life" is because of many decades of shareholder regulation that have been explicitly built up to ban the most common types of abuses. This regulation is, of course, non-"economic" (or, in my lingo, it makes corporate governance less financialized), because it's an explicit attempt to prevent collusion.

Notably, Nathan's favored solutions do not try to regulate coin voting. Instead, they try to limit the harms of its weaknesses by combining it with additional mechanisms:

Rather than relying on direct token voting, as other protocols have done, The Graph uses a board-like mediating layer, the Graph Council, on which the protocol's major stakeholder groups have representatives. In this case, the proposal had the potential to favor one group of stakeholders over others, and passing a decision through the Council requires multiple stakeholder groups to agree. At the same time, the Snapshot vote put pressure on the Council to implement the will of token-holders.

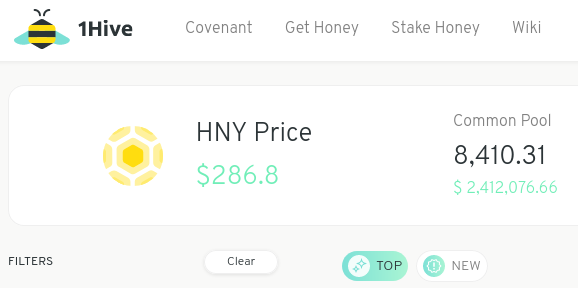

In the case of 1Hive, the anti-financialization protections are described as being purely cultural:

According to a slogan that appears repeatedly in 1Hive discussions, "Come for the honey, stay for the bees." That is, although economics figures prominently as one first encounters and explores 1Hive, participants understand the community's primary value as interpersonal, social, and non-economic.

I am personally skeptical of the latter approach: it can work well in low-economic-value communities that are fun oriented, but if such an approach is attempted in a more serious system with widely open participation and enough at stake to invite determined attack, it will not survive for long. As I wrote above, "any system which claims to be non-finance, but does not actually make an effort to prevent collusion, will eventually acquire the characteristics of finance".

[Edit/correction 2021.09.27: it has been brought to my attention that in addition to culture, financialization is limited by (i) conviction voting, and (ii) juries enforcing a covenant. I'm skeptical of conviction voting in the long run; many DAOs use it today, but in the long term it can be defeated by wrapper tokens. The covenant, on the other hand, is interesting. My fault for not checking in more detail.]

The money is called honey. But is calling money honey enough to make it work differently than money? If not, how much more do you have to do?

The solution in TheGraph is very much an instance of collusion prevention: the participants have been hand-picked to come from diverse constituencies and to be trusted and upstanding people who are unlikely to sell their voting rights. Hence, I am bullish on that approach if it successfully avoids centralization.

So how can we solve these problems more generally?

Nathan's post argues:

A napkin sketch of classical, never-quite-achieved liberal democracy (Brown, 2015) would depict a market (governed through economic incentives) enclosed in politics (governed through deliberation on the common good). Economics has its place, but the system is not economics all the way down; the rules that guide the market, and that enable it in the first place, are decided democratically, on the basis of citizens' civil rights rather than their economic power. By designing democracy into the base-layer of the system, it is possible to overcome the kinds of limitations that cryptoeconomics is vulnerable to, such as by counteracting plutocracy with mass participation and making visible the externalities that markets might otherwise fail to see.

There is one key difference between blockchain political theory and traditional nation-state political theory - and one where, in the long run, nation states may well have to learn from blockchains. Nation-state political theory talks about "markets embedded in democracy" as though democracy is an encompassing base layer that encompasses all of society. In reality, this is not true: there are multiple countries, and every country at least to some degree permits trade with outside countries whose behavior they cannot regulate. Individuals and companies have choices about which countries they live in and do business in. Hence, markets are not just embedded in democracy, they also surround it, and the real world is a complicated interplay between the two.

Blockchain systems, instead of trying to fight this interconnectedness, embrace it. A blockchain system has no ability to regular "the market" in the sense of people's general ability to freely make transactions. But what it can do is regulate and structure (or even create) specific markets, setting up patterns of specific behaviors whose incentives are ultimately set and guided by institutions that have anti-collusion guardrails built in, and can resist pressure from economic actors. And indeed, this is the direction Nathan ends up going in as well. He talks positively about the design of Civil as an example of precisely this spirit:

The aborted Ethereum-based project Civil sought to leverage cryptoeconomics to protect journalism against censorship and degraded professional standards (Schneider, 2020). Part of the system was the Civil Council, a board of prominent journalists who served as a kind of supreme court for adjudicating the practices of the network's newsrooms. Token holders could earn rewards by successfully challenging a newsroom's practices; the success or failure of a challenge ultimately depended on the judgment of the Civil Council, designed to be free of economic incentives clouding its deliberations. In this way, a cryptoeconomic enforcement market served a non-economic social mission. This kind of design could enable cryptoeconomic networks to serve purposes not reducible to economic feedback loops.

This is fundamentally very similar to an idea that I proposed in 2018: prediction markets to scale up content moderation. Instead of doing content moderation by running a low-quality AI algorithm on all content, with lots of false positives, there could be an open mini prediction market on each post, and if the volume got high enough a high-quality committee could step in an adjudicate, and the prediction market participants would be penalized or rewarded based on whether or not they had correctly predicted the outcome. In the mean time, posts with prediction market scores predicting that the post would be removed would not be shown to users who did not explicitly opt-in to participate in the prediction game. There is precedent for this kind of open but accountable moderation: Slashdot meta moderation is arguably a limited version of it. This more financialized version of meta-moderation through prediction markets could produce superior outcomes because the incentives invite highly competent and professional participants to take part.

Nathan then expands:

I have argued that pairing cryptoeconomics with political systems can help overcome the limitations that bedevil cryptoeconomic governance alone. Introducing purpose-centric mechanisms and temporal modulation can compensate for the blind-spots of token economies. But I am not arguing against cryptoeconomics altogether. Nor am I arguing that these sorts of politics must occur in every app and protocol. Liberal democratic theory permits diverse forms of association and business within a democratic structure, and similarly politics may be necessary only at key leverage points in an ecosystem to overcome the limitations of cryptoeconomics alone.

This seems broadly correct. Financialization, as Nathan points out in his conclusion, has benefits in that it attracts a large amount of motivation and energy into building and participating in systems that would not otherwise exist. Furthermore, preventing financialization is very difficult and high cost, and works best when done sparingly, where it is needed most. However, it is also true that financialized systems are much more stable if their incentives are anchored around a system that is ultimately non-financial.

Prediction markets avoid the plutocracy issues inherent in coin voting because they introduce individual accountability: users who acted in favor of what ultimately turns out to be a bad decision suffer more than users who acted against it. However, a prediction market requires some statistic that it is measuring, and measurement oracles cannot be made secure through cryptoeconomics alone: at the very least, community forking as a backstop against attacks is required. And if we want to avoid the messiness of frequent forks, some other explicit non-financialized mechanism at the center is a valuable alternative.

Conclusions

In his conclusion, Nathan writes:

But the autonomy of cryptoeconomic systems from external regulation could make them even more vulnerable to runaway feedback loops, in which narrow incentives overpower the common good. The designers of these systems have shown an admirable capacity to devise cryptoeconomic mechanisms of many kinds. But for cryptoeconomics to achieve the institutional scope its advocates hope for, it needs to make space for less-economic forms of governance.

If cryptoeconomics needs a political layer, and is no longer self-sufficient, what good is cryptoeconomics? One answer might be that cryptoeconomics can be the basis for securing more democratic and values-centered governance, where incentives can reduce reliance on military or police power. Through mature designs that integrate with less-economic purposes, cryptoeconomics might transcend its initial limitations. Politics needs cryptoeconomics, too ... by integrating cryptoeconomics with democracy, both legacies seem poised to benefit.

I broadly agree with both conclusions. The language of collusion prevention can be helpful for understanding why cryptoeconomic purism so severely constricts the design space. "Finance" is a category of patterns that emerge when systems do not attempt to prevent collusion. When a system does not prevent collusion, it cannot treat different individuals differently, or even different numbers of individuals differently: whenever a "position" to exert influence exists, the owner of that position can just sell it to the highest bidder.

Gavels on Amazon. A world where these were NFTs that actually came with associated judging power may well be a fun one, but I would certainly not want to be a defendant!

The language of defense-focused design, on the other hand, is an underrated way to think about where some of the advantages of blockchain-based designs can be. Nation state systems often deal with threats with one of two totalizing mentalities: closed borders vs conquer the world. A closed borders approach attempts to make hard distinctions between an "inside" that the system can regulate and an "outside" that the system cannot, severely restricting flow between the inside and the outside. Conquer-the-world approaches attempt to extraterritorialize a nation state's preferences, seeking a state of affairs where there is no place in the entire world where some undesired activity can happen. Blockchains are structurally unable to take either approach, and so they must seek alternatives.

Fortunately, blockchains do have one very powerful tool in their grasp that makes security under such porous conditions actually feasible: cryptography. Cryptography allows everyone to verify that some governance procedure was executed exactly according to the rules. It leaves a verifiable evidence trail of all actions, though zero knowledge proofs allow mechanism designers freedom in picking and choosing exactly what evidence is visible and what evidence is not. Cryptography can even prevent collusion! Blockchains allow applications to live on a substrate that their governacne does not control, which allows them to effectively implement techniques such as, for example, ensure that every change to the rules only takes effect with a 60 day delay. Finally, freedom to fork is much more practical, and forking is much lower in economic and human cost, than most centralized systems.

Blockchain-based contraptions have a lot to offer the world that other kinds of systems do not. On the other hand, Nathan is completely correct to emphasize that blockchainized should not be equated with financialized. There is plenty of room for blockchain-based systems that do not look like money, and indeed we need more of them.

On Nathan Schneider on the limits of cryptoeconomics

2021 Sep 26 See all postsNathan Schneider has recently released an article describing his perspectives on cryptoeconomics, and particularly on the limits of cryptoeconomic approaches to governance and what cryptoeconomics could be augmented with to improve its usefulness. This is, of course, a topic that is dear to me ([1] [2] [3] [4] [5]), so it is heartening to see someone else take the blockchain space seriously as an intellectual tradition and engage with the issues from a different and unique perspective.

The main question that Nathan's piece is trying to explore is simple. There is a large body of intellectual work that criticizes a bubble of concepts that they refer to as "economization", "neoliberalism" and similar terms, arguing that they corrode democratic political values and leave many people's needs unmet as a result. The world of cryptocurrency is very economic (lots of tokens flying around everywhere, with lots of functions being assigned to those tokens), very neo (the space is 12 years old!) and very liberal (freedom and voluntary participation are core to the whole thing). Do these critiques also apply to blockchain systems? If so, what conclusions should we draw, and how could blockchain systems be designed to account for these critiques? Nathan's answer: more hybrid approaches combining ideas from both economics and politics. But what will it actually take to achieve that, and will it give the results that we want? My answer: yes, but there's a lot of subtleties involved.

What are the critiques of neoliberalism and economic logic?

Near the beginning of Nathan's piece, he describes the critiques of overuse of economic logic briefly. That said, he does not go much further into the underlying critiques himself, preferring to point to other sources that have already covered the issue in depth:

At this point, it's worth pointing out that the "neoliberalism" being criticized here is not the same as the "neoliberalism" that is cheerfully promoted by the lovely folks at The Neoliberal Project; the thing being critiqued here is a kind of "enough two-party trade can solve everything" mentality, whereas The Neoliberal Project favors a mix of markets and democracy. But what is the thrust of the critique that Nathan is pointing to? What's the problem with everyone acting much more like homo oeconomicus? For this, we can take a detour and peek into the source, Wendy Brown's Undoing the Demos, itself. The book helpfully provides a list of the top "four deleterious effects" (the below are reformatted and abridged but direct quotes):

The bulk of Nathan's article follows along with analyses of how these issues affect DAOs and governance mechanisms within the crypto space specifically. Nathan focuses on three key problems:

The natural questions that arise for me are (i) to what extent do I agree with this critique at all and how it fits in with my own thinking, and (ii) how does this affect blockchains, and what do blockchain protocols need to actually do to avoid these traps?

What do I think of the critiques of neoliberalism generally?

I disagree with some, agree with others. I have always been suspicious of criticism of "crass and unethical commercialization", because it frequently feels like the author is attempting to launder their own feelings of disgust and aesthetic preferences into grand ethical and political ideologies - a sin common among all such ideologies, often the right (random example here) even more than the left. Back in the days when I had much less money and would sometimes walk a full hour to the airport to avoid a taxi fare, I remember thinking that I would love to get compensated for donating blood or using my body for clinical trials. And so to me, the idea that such transactions are inhuman exploitation has never been appealing.

But at the same time, I am far from a Walter Block-style defender of all locally-voluntary two-party commerce. I've written up my own viewpoints expressing similar concerns to parts of Wendy Brown's list in various articles:

So where does my own opposition to mixing finance and governance come from? This is a complicated topic, and my conclusions are in large part a result of my own failure after years of attempts to find a financialized governance mechanism that is economically stable. So here goes...

Finance is the absence of collusion prevention

Out of the standard assumptions in what gets pejoratively called "spherical cow economics", people normally tend to focus on the unrealistic nature of perfect information and perfect rationality. But the unrealistic assumption that is hidden in the list that strikes me as even more misleading is individual choice: the idea that each agent is separately making their own decisions, no agent has a positive or negative stake in another agent's outcomes, and there are no "side games"; the only thing that sees each agent's decisions is the black box that we call "the mechanism".

This assumption is often used to bootstrap complex contraptions such as the VCG mechanism, whose theoretical optimality is based on beautiful arguments that because the price each player pays only depends on other players' bids, each player has no incentive to make a bid that does not reflect their true value in order to manipulate the price. A beautiful argument in theory, but it breaks down completely once you introduce the possibility that even two of the players are either allies or adversaries outside the mechanism.

Economics, and economics-inspired philosophy, is great at describing the complexities that arise when the number of players "playing the game" increases from one to two (see the tale of Crusoe and Friday in Murray Rothbard's The Ethics of Liberty for one example). But what this philosophical tradition completely misses is that going up to three players adds an even further layer of complexity. In an interaction between two people, the two can ignore each other, fight or trade. In an interaction between three people, there exists a new strategy: any two of the three can communicate and band together to gang up on the third. Three is the smallest denominator where it's possible to talk about a 51%+ attack that has someone outside the clique to be a victim.

When there's only two people, more coordination can only be good. But once there's three people, the wrong kind of coordination can be harmful, and techniques to prevent harmful coordination (including decentralization itself) can become very valuable. And it's this management of coordination that is the essence of "politics".

Going from two people to three introduces the possibility of harms from unbalanced coordination: it's not just "the individual versus the group", it's "the individual versus the group versus the world".

Now, we can understand try to use this framework to understand the pitfalls of "finance". Finance can be viewed as a set of patterns that naturally emerge in many kinds of systems that do not attempt to prevent collusion. Any system which claims to be non-finance, but does not actually make an effort to prevent collusion, will eventually acquire the characteristics of finance, if not something worse. To see why this is the case, compare two point systems we are all familiar with: money, and Twitter likes. Both kinds of points are valuable for extrinsic reasons, both have inevitably become status symbols, and both are number games where people spend a lot of time optimizing to try to get a higher score. And yet, they behave very differently. So what's the fundamental difference between the two?

The answer is simple: it's the lack of an efficient market to enable agreements like "I like your tweet if you like mine", or "I like your tweet if you pay me in some other currency". If such a market existed and was easy to use, Twitter would collapse completely (something like hyperinflation would happen, with the likely outcome that everyone would run automated bots that like every tweet to claim rewards), and even the likes-for-money markets that exist illicitly today are a big problem for Twitter. With money, however, "I send X to you if you send Y to me" is not an attack vector, it's just a boring old currency exchange transaction. A Twitter clone that does not prevent like-for-like markets would "hyperinflate" into everyone liking everything, and if that Twitter clone tried to stop the hyperinflation by limiting the number of likes each user can make, the likes would behave like a currency, and the end result would behave the same as if Twitter just added a tipping feature.

So what's the problem with finance? Well, if finance is optimized and structured collusion, then we can look for places where finance causes problems by using our existing economic tools to understand which mechanisms break if you introduce collusion! Unfortunately, governance by voting is a central example of this category; I've covered why in the "moving beyond coin voting governance" post and many other occasions. Even worse, cooperative game theory suggests that there might be no possible way to make a fully collusion-resistant governance mechanism.

And so we get the fundamental conundrum: the cypherpunk spirit is fundamentally about making maximally immutable systems that work with as little information as possible about who is participating ("on the internet, nobody knows you're a dog"), but making new forms of governance requires the system to have richer information about its participants and ability to dynamically respond to attacks in order to remain stable in the face of actors with unforeseen incentives. Failure to do this means that everything looks like finance, which means, well.... perennial over-representation of concentrated interests, and all the problems that come as a result.

On the internet, nobody knows if you're 0.0244 of a dog (image source). But what does this mean for governance?

The central role of collusion in understanding the difference between Kleros and regular courts

Now, let us get back to Nathan's article. The distinction between financial and non-financial mechanisms is key in the article. Let us start off with a description of the Kleros court:

The implicit critique is clear: the Kleros court is ultimately motivated to make decisions not on the basis of their "true" correctness or incorrectness, but rather on the basis of their financial interests. If Kleros is deciding whether Biden or Trump won the 2020 election, and one Kleros juror really likes Trump, precommits to voting in his favor, and bribes other jurors to vote the same way, other jurors are likely to fall in line because of Kleros's conformity incentives: jurors are rewarded if their vote agrees with the majority vote, and penalized otherwise. The theoretical answer to this is the right to exit: if the majority of Kleros jurors vote to proclaim that Trump won the election, a minority can spin off a fork of Kleros where Biden is considered to have won, and their fork may well get a higher market price than the original. Sometimes, this actually works! But, as Nathan points out, it is not always so simple:

But alongside the implicit critique is an implicit promise: that regular courts are somehow able to rise above self-interest and "seek a common good together" and thereby avoid some of these failure modes. What is it that financialized Kleros courts lack, but non-financialized regular courts retain, that makes them more robust? One possible answer is that courts lack Kleros's explicit conformity incentive. But if you just take Kleros as-is, remove the conformity incentive (say, there's a reward for voting that does not depend on how you vote), and do nothing else, you risk creating even more problems. Kleros judges could get lazy, but more importantly if there's no incentive at all to choose how you vote, even the tiniest bribe could affect a judge's decision.

So now we get to the real answer: the key difference between financialized Kleros courts and non-financialized regular courts is that financialized Kleros courts are, well... financialized. They make no effort to explicitly prevent collusion. Non-financialized courts, on the other hand, do prevent collusion in two key ways:

The only reason why political and legal systems work is that a lot of hard thinking and work has gone on behind the scenes to insulate the decision-makers from extrinsic incentives, and punish them explicitly if they are discovered to be accepting incentives from the outside. The lack of extrinsic motivation allows the intrinsic motivation to shine through. Furthermore, the lack of transferability allows governance power to be given to specific actors whose intrinsic motivations we trust, avoiding governance power always flowing to "the highest bidder". But in the case of Kleros, the lack of hostile extrinsic motivation cannot be guaranteed, and transferability is unavoidable, and so overpoweringly strong in-mechanism extrinsic motivation (the conformity incentive) was the best solution they could find to deal with the problem.

And of course, the "final backstop" that Kleros relies on, the right of users to fork away, itself depends on social coordination to take place - a messy and difficult institution, often derided by cryptoeconomic purists as "proof of social media", that works precisely because public discussion has lots of informal collusion detection and prevention all over the place.

Collusion in understanding DAO governance issues

But what happens when there is no single right answer that they can expect voters to converge on? This is where we move away from adjudication and toward governance (yes, I know that adjudication has unavoidably grey edge cases too. Governance just has them much more often). Nathan writes:

In my opinion, this actually concedes too much! Governance by economics is not "efficient" once you drop the spherical-cow assumption of no collusion, because it is inherently vulnerable to 51% of the stakeholders colluding to liquidate the company and split its resources among themselves. The only reason why this does not happen much more often "in real life" is because of many decades of shareholder regulation that have been explicitly built up to ban the most common types of abuses. This regulation is, of course, non-"economic" (or, in my lingo, it makes corporate governance less financialized), because it's an explicit attempt to prevent collusion.

Notably, Nathan's favored solutions do not try to regulate coin voting. Instead, they try to limit the harms of its weaknesses by combining it with additional mechanisms:

In the case of 1Hive, the anti-financialization protections are described as being purely cultural:

I am personally skeptical of the latter approach: it can work well in low-economic-value communities that are fun oriented, but if such an approach is attempted in a more serious system with widely open participation and enough at stake to invite determined attack, it will not survive for long. As I wrote above, "any system which claims to be non-finance, but does not actually make an effort to prevent collusion, will eventually acquire the characteristics of finance".

[Edit/correction 2021.09.27: it has been brought to my attention that in addition to culture, financialization is limited by (i) conviction voting, and (ii) juries enforcing a covenant. I'm skeptical of conviction voting in the long run; many DAOs use it today, but in the long term it can be defeated by wrapper tokens. The covenant, on the other hand, is interesting. My fault for not checking in more detail.]

The money is called honey. But is calling money honey enough to make it work differently than money? If not, how much more do you have to do?

The solution in TheGraph is very much an instance of collusion prevention: the participants have been hand-picked to come from diverse constituencies and to be trusted and upstanding people who are unlikely to sell their voting rights. Hence, I am bullish on that approach if it successfully avoids centralization.

So how can we solve these problems more generally?

Nathan's post argues:

There is one key difference between blockchain political theory and traditional nation-state political theory - and one where, in the long run, nation states may well have to learn from blockchains. Nation-state political theory talks about "markets embedded in democracy" as though democracy is an encompassing base layer that encompasses all of society. In reality, this is not true: there are multiple countries, and every country at least to some degree permits trade with outside countries whose behavior they cannot regulate. Individuals and companies have choices about which countries they live in and do business in. Hence, markets are not just embedded in democracy, they also surround it, and the real world is a complicated interplay between the two.

Blockchain systems, instead of trying to fight this interconnectedness, embrace it. A blockchain system has no ability to regular "the market" in the sense of people's general ability to freely make transactions. But what it can do is regulate and structure (or even create) specific markets, setting up patterns of specific behaviors whose incentives are ultimately set and guided by institutions that have anti-collusion guardrails built in, and can resist pressure from economic actors. And indeed, this is the direction Nathan ends up going in as well. He talks positively about the design of Civil as an example of precisely this spirit:

This is fundamentally very similar to an idea that I proposed in 2018: prediction markets to scale up content moderation. Instead of doing content moderation by running a low-quality AI algorithm on all content, with lots of false positives, there could be an open mini prediction market on each post, and if the volume got high enough a high-quality committee could step in an adjudicate, and the prediction market participants would be penalized or rewarded based on whether or not they had correctly predicted the outcome. In the mean time, posts with prediction market scores predicting that the post would be removed would not be shown to users who did not explicitly opt-in to participate in the prediction game. There is precedent for this kind of open but accountable moderation: Slashdot meta moderation is arguably a limited version of it. This more financialized version of meta-moderation through prediction markets could produce superior outcomes because the incentives invite highly competent and professional participants to take part.

Nathan then expands:

This seems broadly correct. Financialization, as Nathan points out in his conclusion, has benefits in that it attracts a large amount of motivation and energy into building and participating in systems that would not otherwise exist. Furthermore, preventing financialization is very difficult and high cost, and works best when done sparingly, where it is needed most. However, it is also true that financialized systems are much more stable if their incentives are anchored around a system that is ultimately non-financial.

Prediction markets avoid the plutocracy issues inherent in coin voting because they introduce individual accountability: users who acted in favor of what ultimately turns out to be a bad decision suffer more than users who acted against it. However, a prediction market requires some statistic that it is measuring, and measurement oracles cannot be made secure through cryptoeconomics alone: at the very least, community forking as a backstop against attacks is required. And if we want to avoid the messiness of frequent forks, some other explicit non-financialized mechanism at the center is a valuable alternative.

Conclusions

In his conclusion, Nathan writes:

I broadly agree with both conclusions. The language of collusion prevention can be helpful for understanding why cryptoeconomic purism so severely constricts the design space. "Finance" is a category of patterns that emerge when systems do not attempt to prevent collusion. When a system does not prevent collusion, it cannot treat different individuals differently, or even different numbers of individuals differently: whenever a "position" to exert influence exists, the owner of that position can just sell it to the highest bidder.

Gavels on Amazon. A world where these were NFTs that actually came with associated judging power may well be a fun one, but I would certainly not want to be a defendant!

The language of defense-focused design, on the other hand, is an underrated way to think about where some of the advantages of blockchain-based designs can be. Nation state systems often deal with threats with one of two totalizing mentalities: closed borders vs conquer the world. A closed borders approach attempts to make hard distinctions between an "inside" that the system can regulate and an "outside" that the system cannot, severely restricting flow between the inside and the outside. Conquer-the-world approaches attempt to extraterritorialize a nation state's preferences, seeking a state of affairs where there is no place in the entire world where some undesired activity can happen. Blockchains are structurally unable to take either approach, and so they must seek alternatives.

Fortunately, blockchains do have one very powerful tool in their grasp that makes security under such porous conditions actually feasible: cryptography. Cryptography allows everyone to verify that some governance procedure was executed exactly according to the rules. It leaves a verifiable evidence trail of all actions, though zero knowledge proofs allow mechanism designers freedom in picking and choosing exactly what evidence is visible and what evidence is not. Cryptography can even prevent collusion! Blockchains allow applications to live on a substrate that their governacne does not control, which allows them to effectively implement techniques such as, for example, ensure that every change to the rules only takes effect with a 60 day delay. Finally, freedom to fork is much more practical, and forking is much lower in economic and human cost, than most centralized systems.

Blockchain-based contraptions have a lot to offer the world that other kinds of systems do not. On the other hand, Nathan is completely correct to emphasize that blockchainized should not be equated with financialized. There is plenty of room for blockchain-based systems that do not look like money, and indeed we need more of them.